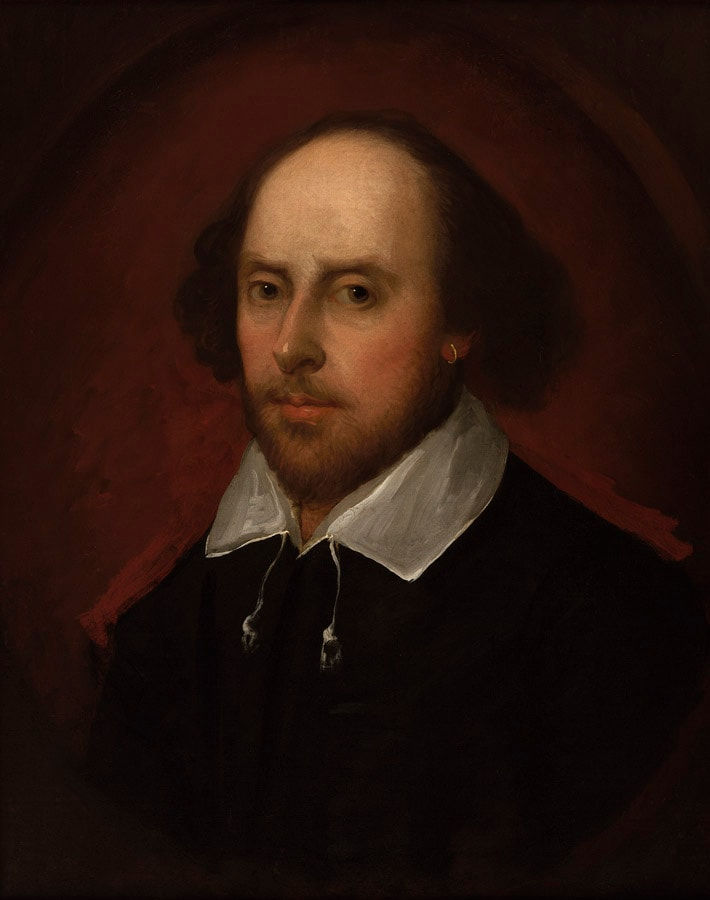

After John Taylor

Portrait of William Shakespeare (1564-1616), 18th Century

Oil on canvas

22 1/2 x 17 3/4 in (57.2 x 45.1 cm)

Philip Mould & Co.

To view all current artworks for sale visit philipmould.com This important portrait is a faithful replica of the well known ‘Chandos’ portrait of Shakespeare [National Portrait Gallery, London], which...

To view all current artworks for sale visit philipmould.com

This important portrait is a faithful replica of the well known ‘Chandos’ portrait of Shakespeare [National Portrait Gallery, London], which is thought to be the only undisputed likeness of the playwright in oil. The present picture was probably painted in the latter half of the eighteenth century, and possibly about the time the original portrait came into the possession of the James Brydges, 3rd Duke of Chandos, who owned it from 1783 onwards.

The validity of the Chandos portrait as showing Shakespeare relies mainly on its apparent early provenance. It has long been accepted as showing Shakespeare, and in the early eighteenth century was recorded by the art historian George Vertue as having belonged to the noted actor Thomas Betterton, and before that Sir William Davenant, who is widely thought to have been Shakespeare’s godson.

Unlike many copies of the Chandos picture, which are most often painted from engravings, this example must have been painted directly from the original portrait. As such, its fresh condition and vibrant colouring perhaps allows us to see what the original portrait may then have looked like, given that the Chandos picture is today so covered in discoloured varnish, over-paint and dirt.

The colouring of the present picture, with its vibrant whites of the collar and more animated modeling of areas such as the hair, gives an idea of how much brighter the Chandos picture must once have appeared. And perhaps more importantly, details of Shakespeare’s physiognomy, such as the outline of his nose, are seen here with greater precision.

In the present picture, for example, the nose is presented as more prominent than it now appears in the original, since most of the dark glazes with which the artist first drew Shakespeare’s outlines have been much abraded. Similarly, comparison between the Chandos picture and the present picture, together with another even earlier replica [Private Collection] shows that the Shakespeare we see in the Chandos picture today has artificially long hair, for in the Guilford version it stops well short of his collar. Likewise, the Chandos Shakespeare today has a pointy beard, which is not evident in the Guilford example.

We do not know who made such additions to the Chandos portrait, but we do know that in the mid-nineteenth century much was made of the fact that the Chandos Shakespeare seemed at odds with contemporary notions of Shakespeare’s image. One critic claimed that the picture showed a man ‘of decidedly Jewish physiognomy… with a coarse expression…’ It is likely, therefore, that additions such as the pointy beard and longer hair were added to the Chandos picture to make Shakespeare look more like the Bohemian playwright history has assumed him to be.

This important portrait is a faithful replica of the well known ‘Chandos’ portrait of Shakespeare [National Portrait Gallery, London], which is thought to be the only undisputed likeness of the playwright in oil. The present picture was probably painted in the latter half of the eighteenth century, and possibly about the time the original portrait came into the possession of the James Brydges, 3rd Duke of Chandos, who owned it from 1783 onwards.

The validity of the Chandos portrait as showing Shakespeare relies mainly on its apparent early provenance. It has long been accepted as showing Shakespeare, and in the early eighteenth century was recorded by the art historian George Vertue as having belonged to the noted actor Thomas Betterton, and before that Sir William Davenant, who is widely thought to have been Shakespeare’s godson.

Unlike many copies of the Chandos picture, which are most often painted from engravings, this example must have been painted directly from the original portrait. As such, its fresh condition and vibrant colouring perhaps allows us to see what the original portrait may then have looked like, given that the Chandos picture is today so covered in discoloured varnish, over-paint and dirt.

The colouring of the present picture, with its vibrant whites of the collar and more animated modeling of areas such as the hair, gives an idea of how much brighter the Chandos picture must once have appeared. And perhaps more importantly, details of Shakespeare’s physiognomy, such as the outline of his nose, are seen here with greater precision.

In the present picture, for example, the nose is presented as more prominent than it now appears in the original, since most of the dark glazes with which the artist first drew Shakespeare’s outlines have been much abraded. Similarly, comparison between the Chandos picture and the present picture, together with another even earlier replica [Private Collection] shows that the Shakespeare we see in the Chandos picture today has artificially long hair, for in the Guilford version it stops well short of his collar. Likewise, the Chandos Shakespeare today has a pointy beard, which is not evident in the Guilford example.

We do not know who made such additions to the Chandos portrait, but we do know that in the mid-nineteenth century much was made of the fact that the Chandos Shakespeare seemed at odds with contemporary notions of Shakespeare’s image. One critic claimed that the picture showed a man ‘of decidedly Jewish physiognomy… with a coarse expression…’ It is likely, therefore, that additions such as the pointy beard and longer hair were added to the Chandos picture to make Shakespeare look more like the Bohemian playwright history has assumed him to be.

Provenance

The North family, the Earls of Guilford, and by descent.Be the first to hear about our available artworks

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied in accordance with our privacy policy (available on request). You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.