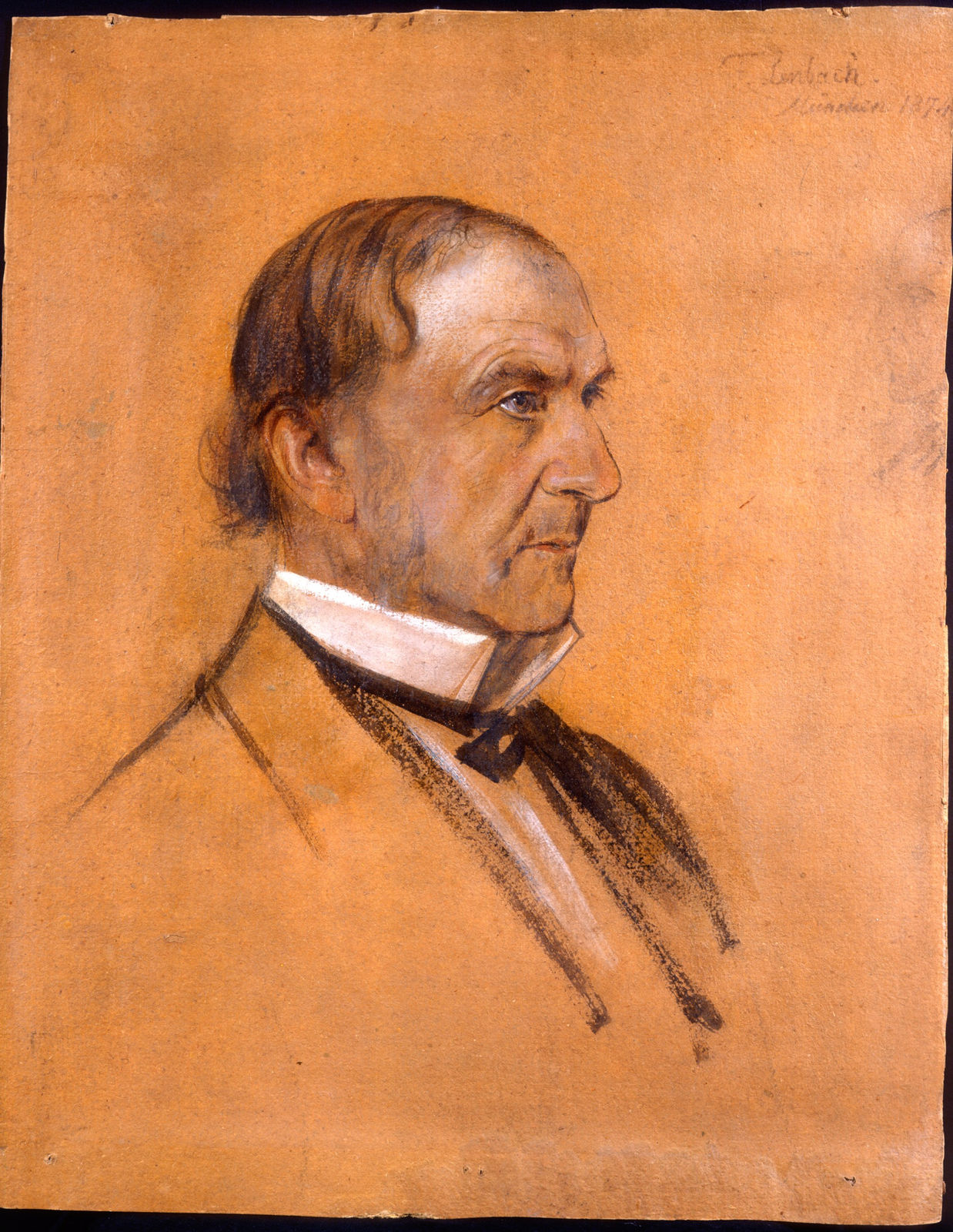

Franz von Lenbach

Portrait sketch of William Ewart Gladstone (1809-98), 1874

Oil on board

26 x 22 in. (65.5 x 55.5 cm)

Philip Mould & Co.

To view all current artworks for sale visit philipmould.com This life study of the Prime Minister William Gladstone was painted in 1874, shortly after his first term in office,...

To view all current artworks for sale visit philipmould.com

This life study of the Prime Minister William Gladstone was painted in 1874, shortly after his first term in office, from which he resigned at the Conservative victory in the General Election of February 17th 1874. It is important in two respects, since it is not only a rare example of a portrait of Gladstone painted abroad by a foreign artist, but it is also the work of the most modern painter to whom the Prime Minister sat. The sketch is preparatory to two larger portraits that Lenbach painted of Gladstone. One portrays Gladstone seated three-quarter length in a chair, in a pose reminiscent of the later portrait in doctoral robes by Sir John Everett Millais (Christ Church, Oxford). The second portrait is an unusual seated double portrait of Gladstone with the Bavarian Catholic controversialist and royal councillor Ignaz Döllinger, which lacks the animation and the sheer presence of this life sketch. The degree of observation achieved in this sketch is unsurpassed in Gladstone’s portraiture, even in the work of those painters to whom he sat on several occasions, and the meticulous record of detail has an almost photographic quality. To view the sketch is not only to observe the man but to enter his presence.

Although Döllinger had been a councillor to the Bavarian King Maximilian II and a representative at the Frankfurt Parliament, the interest that the two men shared was less political than theological, although the two concerns were perhaps not easily distinguished. In 1870 Pope Pius XI proclaimed the doctrine of Papal Infallibility. Döllinger wrote against this doctrine, and sought the support of fellow-opponents in Germany and abroad. He had always enjoyed close links with England, and it was natural that he should find an ally in Gladstone. In the year of this portrait, Gladstone had published an article in the Contemporary Review in which he questioned the universal obedience that the Catholic Church demanded of its members above their national loyalties. At a time when much of European politics were in a ferment of burgeoning nationalism, the claims of the Vatican were seen by many as incompatible with the autonomy of the nation state. The Lenbach portrait, therefore, is an important record of an often forgotten aspect of nineteenth century European politics dating from perhaps the last period that the Vatican was able to play a commanding role on the diplomatic stage.

By the end of the nineteenth century, Lenbach was the chief portraitist to the aristocratic and political elite of Germany. His sitters included King Ludwig I of Bavaria, Kaiser Frederick, Field Marshal von Moltke as well as the ‘Iron Chancellor’ Prince Bismarck, whom he painted numerous times. As the iconographer of the powerful alone he would be a figure worthy of note, but his most important legacy is his development of what was to become the international style of grand manner portraiture by the late nineteenth century. The sources for his style were various, and he seems to have chosen the mode of representation according to his subject. The portrait painted in 1901 of his daughter Gabriele, for example, is a swiftly captured study that deliberately recalls Frans Hals’s Laughing Boy, and an earlier portrait of the young girl in seventeenth century dress maked the allusion explicit. In his portraits of statesmen, however, he would seem to have looked more to Van Dyck. Again, an explicit reference to Van Dyck in his Triple Portrait of Prince Bismarck suggests Van Dyck’s Triple Portrait of King Charles I, and casts a flattering light on both painter and subject.

It is in his sketches, and in his portraits of women that he initiates many of the conventions that were to be followed by his successors. The apparent artlessness of the presentation of the present sketch of Gladstone may be genuine or feigned. The portrait could stand as a finished work in its own right, although the faint presence of a second pencil profile to the right suggests that this is indeed a preparatory rather than a presentation work, but it is a technique that was to be taken up enthusiastically by Philip de Laszlo, who was a great admirer of the German painter’s work. In his female portraiture his is conspicuously indebted to Gainsborough and British eighteenth century portraiture, and he demonstrates the elegant and grandiose ‘broad brush’ manner that was to reach perfection in the painting of John Singer Sargent.

This life study of the Prime Minister William Gladstone was painted in 1874, shortly after his first term in office, from which he resigned at the Conservative victory in the General Election of February 17th 1874. It is important in two respects, since it is not only a rare example of a portrait of Gladstone painted abroad by a foreign artist, but it is also the work of the most modern painter to whom the Prime Minister sat. The sketch is preparatory to two larger portraits that Lenbach painted of Gladstone. One portrays Gladstone seated three-quarter length in a chair, in a pose reminiscent of the later portrait in doctoral robes by Sir John Everett Millais (Christ Church, Oxford). The second portrait is an unusual seated double portrait of Gladstone with the Bavarian Catholic controversialist and royal councillor Ignaz Döllinger, which lacks the animation and the sheer presence of this life sketch. The degree of observation achieved in this sketch is unsurpassed in Gladstone’s portraiture, even in the work of those painters to whom he sat on several occasions, and the meticulous record of detail has an almost photographic quality. To view the sketch is not only to observe the man but to enter his presence.

Although Döllinger had been a councillor to the Bavarian King Maximilian II and a representative at the Frankfurt Parliament, the interest that the two men shared was less political than theological, although the two concerns were perhaps not easily distinguished. In 1870 Pope Pius XI proclaimed the doctrine of Papal Infallibility. Döllinger wrote against this doctrine, and sought the support of fellow-opponents in Germany and abroad. He had always enjoyed close links with England, and it was natural that he should find an ally in Gladstone. In the year of this portrait, Gladstone had published an article in the Contemporary Review in which he questioned the universal obedience that the Catholic Church demanded of its members above their national loyalties. At a time when much of European politics were in a ferment of burgeoning nationalism, the claims of the Vatican were seen by many as incompatible with the autonomy of the nation state. The Lenbach portrait, therefore, is an important record of an often forgotten aspect of nineteenth century European politics dating from perhaps the last period that the Vatican was able to play a commanding role on the diplomatic stage.

By the end of the nineteenth century, Lenbach was the chief portraitist to the aristocratic and political elite of Germany. His sitters included King Ludwig I of Bavaria, Kaiser Frederick, Field Marshal von Moltke as well as the ‘Iron Chancellor’ Prince Bismarck, whom he painted numerous times. As the iconographer of the powerful alone he would be a figure worthy of note, but his most important legacy is his development of what was to become the international style of grand manner portraiture by the late nineteenth century. The sources for his style were various, and he seems to have chosen the mode of representation according to his subject. The portrait painted in 1901 of his daughter Gabriele, for example, is a swiftly captured study that deliberately recalls Frans Hals’s Laughing Boy, and an earlier portrait of the young girl in seventeenth century dress maked the allusion explicit. In his portraits of statesmen, however, he would seem to have looked more to Van Dyck. Again, an explicit reference to Van Dyck in his Triple Portrait of Prince Bismarck suggests Van Dyck’s Triple Portrait of King Charles I, and casts a flattering light on both painter and subject.

It is in his sketches, and in his portraits of women that he initiates many of the conventions that were to be followed by his successors. The apparent artlessness of the presentation of the present sketch of Gladstone may be genuine or feigned. The portrait could stand as a finished work in its own right, although the faint presence of a second pencil profile to the right suggests that this is indeed a preparatory rather than a presentation work, but it is a technique that was to be taken up enthusiastically by Philip de Laszlo, who was a great admirer of the German painter’s work. In his female portraiture his is conspicuously indebted to Gainsborough and British eighteenth century portraiture, and he demonstrates the elegant and grandiose ‘broad brush’ manner that was to reach perfection in the painting of John Singer Sargent.

5

of

5