Nicholas Hilliard

Further images

To view all current artworks for sale visit philipmould.com

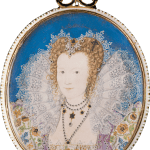

This portrait miniature or ‘limning’ is an exemplary example from the latter part of the reign of Elizabeth I and the mature style of Nicholas Hilliard. Although stylised and precisely drawn, the portrait includes humanising elements which look toward the greater characterisation and naturalisation found in the later seventeenth century portrait. Among the starched court finery of the sitter, her auburn curls escape, teased out by Hilliard onto her ruff. As Erna Auerbach notes of this portrait; “An almost Rococo treatment of the hair, with corkscrew curls falling down onto the standing lace ruff, distinguishes the miniature”.[1]

As might be expected from the hand of Elizabeth I’s own image-maker, this portrait of a young married lady is laden with symbolism. Using the backdrop of the sitter’s hair and dress, Hilliard has interweaved an opus of symbolic objects. The status of the portrait miniature in Elizabethan England was ostensibly that of a private image. As part of a complex world ruled by courtly conventions they were used as a form of communication, their use controlled by their owner. To this end, portrait miniatures, or limnings as they were then known, were imbued with emblems personal and significant to owner and recipient. As Clifford Geertz has observed, the Elizabethan imagination was “allegorical, Protestant, didactic, and pictorial; it lived on moral abstractions cast into emblems.”[2] From the 1580s onwards, female court dress began to incorporate these emblems as embroidery.

The present example is no exception and to the Elizabethan eye this miniature would have read as a litany to the virtues of a young wife and mother. The jewelled crossbow nestled in the sitter’s auburn hair, for example, is a symbol of brains over brute strength.[3] Although uncommon, if known at all, in other portraits by Hilliard, this symbol notably appears in the oil portrait of the young Anne of Denmark [after Paul van Somer, 1617/18, National Portrait Gallery, London]. Similarly shown housed in the Queen’s coiffure, this jewel may have been the same one as Anne inherited from Elizabeth I.[4]

Although not firmly identifiable at present, the sitter is presenting to the viewer a close connection with Elizabeth’s court. It is well documented that Elizabeth was donating items from her wardrobe from 1561 until the end of her reign. Janet Arnold has suggested that many of these court ladies may have had their portraits painted in appreciation of such gifts, although her theory does not embrace the more private portrait miniature type.[5] The inclusion of the Tudor rose, prominent in the centre of the sitter’s bodice and embroidered irises, found in other dresses worn by Elizabeth would suggest an alliance with the Queen.[6] The addition of oak leaves embroidered on the sleeves can also be seen in other portraits of Elizabeth[7]

[1] Erna Auerbach, Nicholas Hilliard, 1961, p. 109

[2] Clifford Geertz, “Centers, Kings and Charisma; Reflections on the Symbolism of Power”, in Rites of Power: Symbolism, Ritual and Politics since the Middle Ages, Sean Wilentz, ed. (Philadelphia, 1985), p.19

[3] Books of emblems were popular at the end of the sixteenth century and the crossbow is included in Geoffrey Witney, A Choice of Emblemes, pub. Leyden 1586

[4] The 1606 inventory Queen Anne of Denmark's jewellery (National Library of Scotland; for which see D. Scarisbrick 'Anne of Denmark's Jewellery Inventory', Archaeologia, CIX, 1991), includes for example 'A Jewell in the form of a Crossbow, bent with gold with a harte enameled redde at the string, garnished with a small Table Diamonde & one small pointed Diamond', which Janet Arnold suggested may be identifiable with that listed among Queen Elizabeth I's jewels in 1600: 'a jewel of gold like a crossbow garnished with diamonds'; which was among the jewels taken by King James I after his accession.

[5] Janet Arnold, Queen Elizabeth I’s Wardrobe Unlock’d, London, 1988

[6] See, for example, Hilliard’s earliest portrait of Elizabeth I, dated 1572, with irises embroidered on the sleeves of her gown [NPG, London]

[7] Both oak leaves and pomegranates are included in The Hampden Portrait of Elizabeth I, dating to the early 1560s [Private Collection, previously at Philip Mould Ltd]

Provenance

Probably Baron Gustave de Rothschild;By whom probably left to Sir Philip Sassoon, 3rd Bt.;

Sybil Sassoon (1894-1989), Marchioness of Cholmondeley;

By whom sold Christie's, London, 22nd October 1974, lot.69 for £17,000;

Spink & Son;

Private Collection, UK.

Exhibitions

‘Hilliard and Oliver’, Victoria and Albert Museum, 1947, no. 45‘The Houghton Pictures’, Agnews, May 6 – June 6 1959, no. 30

Literature

Auerbach, E. Nicholas Hilliard, London, 1961. pg.108 (illustrated), p.g.311.Reynolds, G. Nicholas Hilliard and Isaac Oliver, London, 1971, no.45.