Clara Birnberg

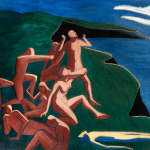

Dawn, c. 1912

Oil on canvas

40 x 57 in. (101.6 x 144.8 cm)

Signed with monogram lower left

Philip Mould & Co.

Further images

To view all current artworks for sale visit philipmould.com Clara Birnberg was the epitome of a ‘new woman’; a member of the Women’s Freedom League suffragette movement, pacifist, vegetarian and...

To view all current artworks for sale visit philipmould.com

Clara Birnberg was the epitome of a ‘new woman’; a member of the Women’s Freedom League suffragette movement, pacifist, vegetarian and pioneering artist working during a tempestuous time in Britian’s history. Her work has been aptly described by Sarah MacDougall, the Head of Collections at the Ben Uri Gallery and Museum, as reflecting ‘the national gulf between the forward movement of emerging modernist art and the traditionalism at the heart of the war effort and society at the time.’[1] This work, completed in the years immediately preceding World War I, demonstrates Birnberg’s artistic positioning at the very forefront of British Modernism.

Birnberg (who later married Stephen Weinstein and then anglicised her name to Clare Winsten), was born in Romania 1894 to Galician Jewish parents Michael and Fanny Birnberg (nee Feige Zallermayer), who fled the pogroms travelling via Romania and later Germany. In c.1902, Birnberg and her family immigrated to London’s East End. It was within this East End Jewish community, centred around Whitechapel and Stepney, that Birnberg thrived and gained recognition within a group of emerging young artists.

After gaining a scholarship from the London County Council, Birnberg attended the Royal Female School of Art, before she transferred to the Slade School of Fine Art in 1910 aged 18. Her years at the Slade coincided with Roger Fry’s two seminal Post-impressionist exhibitions; the significant influence of which is starkly apparent in her early works.[2] At the Slade, Birnberg surrounded herself with painters and sculptors whose work would equally become heavily influenced by European modernism - particularly Cubism, Fauvism and Futurism. She became the only female member of a group of 14 artists known as the ‘Whitechapel Boys’, a Jewish group of artists and writers whose experimentation with abstracted and geometric forms became highly influential in the development of British Modernism. Determined and strong willed, Birnberg held her own in the male dominated group which included artists such as Jacob Epstein, Isaac Rosenberg and David Bomberg. Much like the Whitechapel writers, she has been referred to as ‘poor, talented, ambition and vocal … also overtly political.’[3]

Her work was exhibited in the 1914 Whitechapel Art Gallery exhibition 'Twentieth Century Art: A Review of Modern Movements'. The exhibition included a so-called ‘Jewish Section’, curated by David Bomberg who brought together works by 15 different Jewish artists, the majority of which he and Birnberg studied with at the Slade. She was one of only two artists to be included both within and out of the much-debated ‘Jewish Section’.[4] The wide-ranging exhibition also included a section which highlighted a display of works from the Omega workshops, where Birnberg worked for in 1913 for short period, after she left the Slade. Garnering interest in the press, an article in The Times referenced the exhibition; ‘Art and Reality | Challenge of Whitechapel to Piccadilly’ stated that ‘Art, like life, is at any rate more exciting in Whitechapel than Piccadilly. Something is happening there and nothing at all at Burlington House … And it must at any rate make those who visit it aware that there is a new movement violently different from anything in the last century. … and whether you like it or dis- like it you must admit that nearly every young man of talent belongs to it.’[5]

The present painting was likely completed during, or just after she finished her studies at the Slade, and around the time of the 1914 Whitechapel Gallery exhibition. The geometric forms, bold palette and dynamic impulse are indicative of the influence of Post-Impressionism and Birnberg’s radical engagement with British modernism. Birnberg here demonstrates her interest in classical and biblical narratives, likely encouraged at the Slade, whilst simultaneously pushing against the constraints of traditional representation. The relation of figures to one another, both compositionally and emotionally, is taut. As a result, each figure expresses disparate emotions and individual compositional autonomy; anger, extreme misery, exhaustion, compassion are conveyed with conviction through Birnberg’s bold strokes of paint. Emboldened by the likes of European modernists such as Gauguin, Cezanne and Picasso, Birnberg here seems to reconfigure traditional representations of bathers - a recurring trope throughout the history of art. Birnberg’s controlled arrangement of figures and use of perspective somewhat adheres to the composition of Renaissance masterpieces, such as Titan’s paintings depicting the Mythological tale of Actaeon and Diana in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. However, the dramatic-cliff top which divides the canvas, the simplified and angular figures, bold colour choices and slight distortion of perspective celebrate the hight of modern art of the new century.

During the First World War, Birnberg married the artist and writer Stephen Weinstein. Both pacifists, Weinstein was imprisoned for three years as a conscientious objector, whilst Birnberg gave birth to the first of the couple’s two daughters. They later anglicized their name to Winsten and embraced Quaker humanism.[6] After the war, Winsten’s style grew increasingly figurative; she drew prominent contemporary figures such as George Bernard Shaw (National Portrait Gallery; NPG 6891) and Mahatma Gandhi. Works by Winsten can be found in the collections at the National Portrait gallery and the Ben Uri Gallery.

[1] S. MacDougall, ‘Biographies’ in (ed. S. Llewellyn) Fifty Works by Fifty British Women Artists 1900-1950 (London: Empress Litho, 2018) p.181.

[2] S. MacDougall, ‘A newly-discovered portrait of Joseph Leftwich by ‘Whitechapel Girl’ Clare Winsten’, British Portraits [available at: https://www.britishportraits.org.uk/blog/a-newly-discovered-portrait-of-joseph-leftwich-by-whitechapel-girl-clare-winsten-c-1919/] (Accessed on 18th September 2020).

[3] S. MacDougall, ‘Whitechapel Girl’ in (eds. S. MacDougall & R. Dickenson) Whitechapel at War (Verona: Graphicom, 2008) p.99.

[4] S. MacDougall, ‘Whitechapel Girl’ in (eds. S. MacDougall & R. Dickenson) Whitechapel at War (Verona: Graphicom, 2008) p.108.

[5] ‘Art and Reality’, The Times (14th May 1914) [available at https://www.thetimes.co.uk/archive/article/1914-05-08/4/7.html#start=1914-05-07&end=1914-05-09&terms=whitechapel&back=/tto/archive/find/whitechapel/w:1914-05-07~1914-05-09/1] (Accessed on 4th October 2020).

[6] S. MacDougall, ‘A newly-discovered portrait of Joseph Leftwich by ‘Whitechapel Girl’ Clare Winsten’, British Portraits [available at: https://www.britishportraits.org.uk/blog/a-newly-discovered-portrait-of-joseph-leftwich-by-whitechapel-girl-clare-winsten-c-1919/] (Accessed on 18th September 2020).

Clara Birnberg was the epitome of a ‘new woman’; a member of the Women’s Freedom League suffragette movement, pacifist, vegetarian and pioneering artist working during a tempestuous time in Britian’s history. Her work has been aptly described by Sarah MacDougall, the Head of Collections at the Ben Uri Gallery and Museum, as reflecting ‘the national gulf between the forward movement of emerging modernist art and the traditionalism at the heart of the war effort and society at the time.’[1] This work, completed in the years immediately preceding World War I, demonstrates Birnberg’s artistic positioning at the very forefront of British Modernism.

Birnberg (who later married Stephen Weinstein and then anglicised her name to Clare Winsten), was born in Romania 1894 to Galician Jewish parents Michael and Fanny Birnberg (nee Feige Zallermayer), who fled the pogroms travelling via Romania and later Germany. In c.1902, Birnberg and her family immigrated to London’s East End. It was within this East End Jewish community, centred around Whitechapel and Stepney, that Birnberg thrived and gained recognition within a group of emerging young artists.

After gaining a scholarship from the London County Council, Birnberg attended the Royal Female School of Art, before she transferred to the Slade School of Fine Art in 1910 aged 18. Her years at the Slade coincided with Roger Fry’s two seminal Post-impressionist exhibitions; the significant influence of which is starkly apparent in her early works.[2] At the Slade, Birnberg surrounded herself with painters and sculptors whose work would equally become heavily influenced by European modernism - particularly Cubism, Fauvism and Futurism. She became the only female member of a group of 14 artists known as the ‘Whitechapel Boys’, a Jewish group of artists and writers whose experimentation with abstracted and geometric forms became highly influential in the development of British Modernism. Determined and strong willed, Birnberg held her own in the male dominated group which included artists such as Jacob Epstein, Isaac Rosenberg and David Bomberg. Much like the Whitechapel writers, she has been referred to as ‘poor, talented, ambition and vocal … also overtly political.’[3]

Her work was exhibited in the 1914 Whitechapel Art Gallery exhibition 'Twentieth Century Art: A Review of Modern Movements'. The exhibition included a so-called ‘Jewish Section’, curated by David Bomberg who brought together works by 15 different Jewish artists, the majority of which he and Birnberg studied with at the Slade. She was one of only two artists to be included both within and out of the much-debated ‘Jewish Section’.[4] The wide-ranging exhibition also included a section which highlighted a display of works from the Omega workshops, where Birnberg worked for in 1913 for short period, after she left the Slade. Garnering interest in the press, an article in The Times referenced the exhibition; ‘Art and Reality | Challenge of Whitechapel to Piccadilly’ stated that ‘Art, like life, is at any rate more exciting in Whitechapel than Piccadilly. Something is happening there and nothing at all at Burlington House … And it must at any rate make those who visit it aware that there is a new movement violently different from anything in the last century. … and whether you like it or dis- like it you must admit that nearly every young man of talent belongs to it.’[5]

The present painting was likely completed during, or just after she finished her studies at the Slade, and around the time of the 1914 Whitechapel Gallery exhibition. The geometric forms, bold palette and dynamic impulse are indicative of the influence of Post-Impressionism and Birnberg’s radical engagement with British modernism. Birnberg here demonstrates her interest in classical and biblical narratives, likely encouraged at the Slade, whilst simultaneously pushing against the constraints of traditional representation. The relation of figures to one another, both compositionally and emotionally, is taut. As a result, each figure expresses disparate emotions and individual compositional autonomy; anger, extreme misery, exhaustion, compassion are conveyed with conviction through Birnberg’s bold strokes of paint. Emboldened by the likes of European modernists such as Gauguin, Cezanne and Picasso, Birnberg here seems to reconfigure traditional representations of bathers - a recurring trope throughout the history of art. Birnberg’s controlled arrangement of figures and use of perspective somewhat adheres to the composition of Renaissance masterpieces, such as Titan’s paintings depicting the Mythological tale of Actaeon and Diana in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. However, the dramatic-cliff top which divides the canvas, the simplified and angular figures, bold colour choices and slight distortion of perspective celebrate the hight of modern art of the new century.

During the First World War, Birnberg married the artist and writer Stephen Weinstein. Both pacifists, Weinstein was imprisoned for three years as a conscientious objector, whilst Birnberg gave birth to the first of the couple’s two daughters. They later anglicized their name to Winsten and embraced Quaker humanism.[6] After the war, Winsten’s style grew increasingly figurative; she drew prominent contemporary figures such as George Bernard Shaw (National Portrait Gallery; NPG 6891) and Mahatma Gandhi. Works by Winsten can be found in the collections at the National Portrait gallery and the Ben Uri Gallery.

[1] S. MacDougall, ‘Biographies’ in (ed. S. Llewellyn) Fifty Works by Fifty British Women Artists 1900-1950 (London: Empress Litho, 2018) p.181.

[2] S. MacDougall, ‘A newly-discovered portrait of Joseph Leftwich by ‘Whitechapel Girl’ Clare Winsten’, British Portraits [available at: https://www.britishportraits.org.uk/blog/a-newly-discovered-portrait-of-joseph-leftwich-by-whitechapel-girl-clare-winsten-c-1919/] (Accessed on 18th September 2020).

[3] S. MacDougall, ‘Whitechapel Girl’ in (eds. S. MacDougall & R. Dickenson) Whitechapel at War (Verona: Graphicom, 2008) p.99.

[4] S. MacDougall, ‘Whitechapel Girl’ in (eds. S. MacDougall & R. Dickenson) Whitechapel at War (Verona: Graphicom, 2008) p.108.

[5] ‘Art and Reality’, The Times (14th May 1914) [available at https://www.thetimes.co.uk/archive/article/1914-05-08/4/7.html#start=1914-05-07&end=1914-05-09&terms=whitechapel&back=/tto/archive/find/whitechapel/w:1914-05-07~1914-05-09/1] (Accessed on 4th October 2020).

[6] S. MacDougall, ‘A newly-discovered portrait of Joseph Leftwich by ‘Whitechapel Girl’ Clare Winsten’, British Portraits [available at: https://www.britishportraits.org.uk/blog/a-newly-discovered-portrait-of-joseph-leftwich-by-whitechapel-girl-clare-winsten-c-1919/] (Accessed on 18th September 2020).